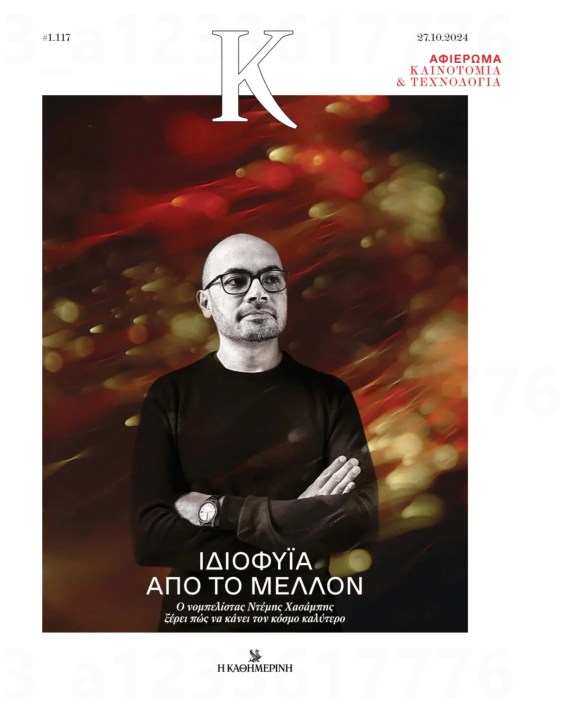

This is the English translation of a K Magazine article from the Kathimerini newspaper, published in print on October 27, 2024, and online on October 31, 2024

WHEN THE ROCK APOCALYPSE OCCURED

By Vyronas Kritzas

There's an old interview of Vangelis Papathanassiou on YouTube which was aired on ERT1 in 1990. Towards the end, the composer performs a grandiose piece on the synthesizer, wearing dark sunglasses in a dim room. In the imposing finale, in estrus, Papathanassiou jumps from his seat, exclaims twice, "I can't anymore," claps his hands, and then places them on his head. "Where do you draw all this magic from, Mr. Papathanassiou?" the enchanted reporter asks. But Vangelis isn’t in the mood for a conversation. He communicates with the sound engineer and then walks away from the instrument as if he had just experienced something ecstatic.

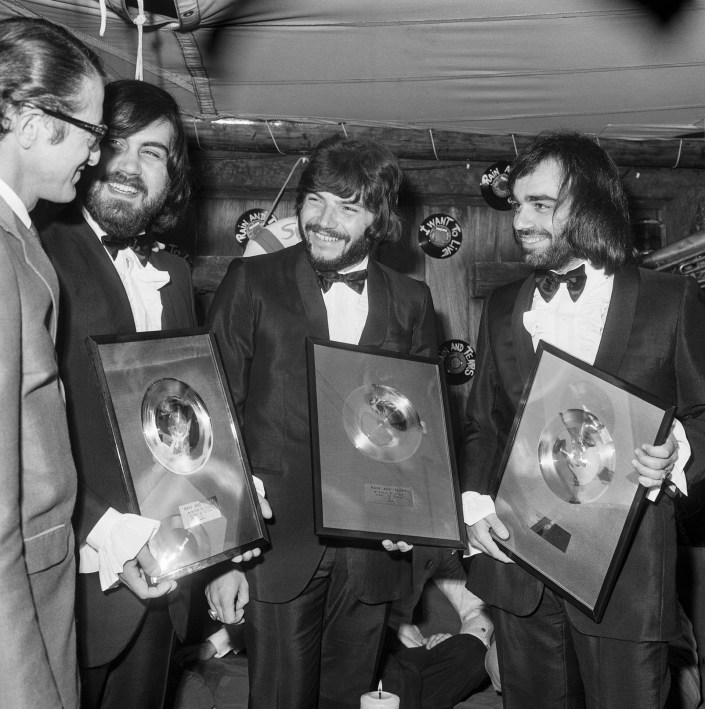

The album 666 by Aphrodite’s Child, recently re-released in a meticulous remastered edition by Universal, marked Vangelis Papathanassiou’s first major artistic gesture. This was the moment he stopped being just a pop/rock hitmaker and started flirting with metaphysics, philosophy, and avant-garde. It remains the only Greek rock album recognised internationally, it consists a treasure trove for countless music lovers around the world, and a reflection of the extravagance of the then-thriving progressive rock. Released by the British label Vertigo in 1972, it didn’t initially make a splash in terms of sales (achieving recognition only over time), quickly became a cult favorite, and laid the foundations for the significant solo careers of Papathanassiou and Demis Roussos. But let’s take things from the beginning.

"There was GOOD CHEMISTRY in that group from the start. We communicated with our eyes. And, of course, there was Vangelis' incredible music." -Loukás Sideras

Greece-France

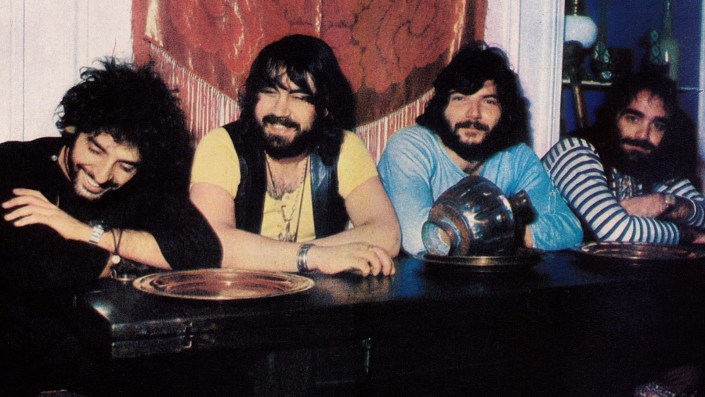

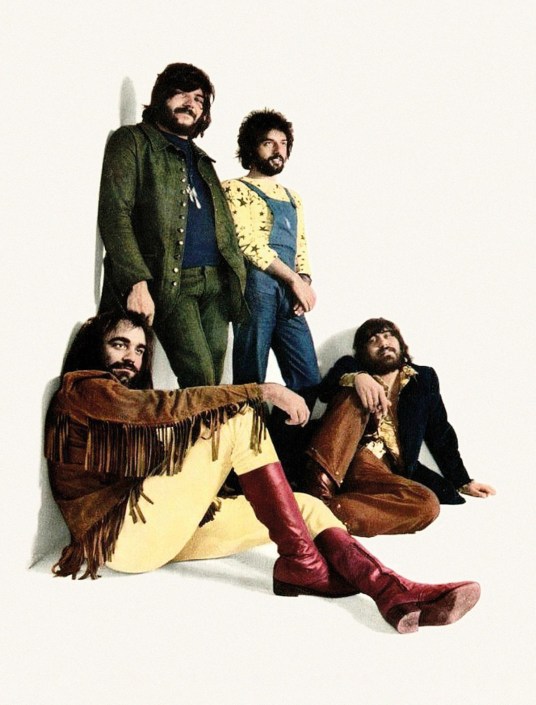

Vangelis Papathanassiou and Demis Roussos met in the mid-’60s as musicians in pop bands in Athens. The former played keyboards and organ in The Forminx, while the latter played bass in The Idols. Along with the drummer Loukás Sideras and the guitarist Argyris "Silver" Koulouris, the band (yet unnamed or sometimes called The Papathanassiou Set) began moving towards a mature psychedelic rock sound, performing in bars like Galaxy at the Hilton. “The goal was to save some money and go abroad,” recalls drummer Loukás Sideras. "Otherwise, there was good chemistry in the group. We communicated with our eyes. And of course, there was Vangelis’ incredible music. Today, it’s hard to understand what it meant to compose sounds like that without computers." Papathanassiou was already a "figure" on the local scene. A characteristic quote from producer Nikos Mastorakis in Modern Rhythms magazine in January 1967 goes, "Any musician would give up everything to play with Vangelis."

In the spring of 1968, amid the Greek military junta, the group decided to make a bold move and head to England. However, they faced two obstacles: first, guitarist Argyris Koulouris had to stay behind to complete his military service, and second, the members lacked work permits. “At the border in Dover, Demis and I weren’t allowed to pass,” Sideras remembers. “So we went to Paris, waiting for Vangelis to join us and figure out what to do.” Eventually, they settled there, signed with Mercury, named themselves Aphrodite’s Child (after the homonym song by Dick Campbell), and released the single Rain and Tears, which became linked with the events of May ’68 and was an instant hit in France and other European countries.

The first two albums, End of the World (1968) and It’s Five O’Clock (1969), established their reputation, with notable tracks like Spring, Summer, Winter, and Fall (1970). Meanwhile, Papathanassiou, who had always avoided flying, began losing interest in the suffering and obbligations of a rock band and focused on composing film music. The atmosphere grew tense. Demis Roussos plans his solo career. Yet, the band owed Mercury one more album. Papathanassiou wanted to close the chapter of Aphrodite’s Child with a project that would establish him as a serious composer. So, he asked his friend Kostas Ferris to provide lyrics for a set of songs with a unified theme. Concept albums, such as The Who’s rock opera Tommy, were in vogue at the time.

The Album

The first thing people learn about 666—and find intimidating, to say the least—is that the lyrics and texts are based on the Apocalypse of John. Of course, it's all aligned with the spirit and demands of the time: May ’68, the hippie movement, and the revolutionary nature of rock coexisted with the prophecies and eschatology of the New Testament. On the other hand, not everything is as serious as it seems.

“Today, we can review it. Back then, we didn’t have time for review. It was something NATURAL.” -Argyris Koulouris

“We constantly had a sense of humor about the work, something that was almost never recognised,” notes Kostas Ferris in a recent interview in Newsbomb. “We were always laughing; it’s not a serious work—it’s a self-mocking satire of the Apocalypse.”

The recordings began in late 1970 at Europa Sonor Studios in Paris. “The atmosphere was somehow electrified,” Koulouris recalls. “There were disagreements because we didn’t know where we were heading. You’d play one piece, and another would pop up. We were experimenting with different instruments, different sounds… It was a bit of ‘wait your turn.’” The recording sessions eventually lasted for three months, with some sources suggesting they exceeded six. “We had sold millions of records,” explains Sideras. “So, we had the luxury of spending hours upon hours in the studio, and we took full advantage of it. Since we knew Phillips wouldn’t like the album (they’d find it uncommercial), we forbade them from listening to it.” In this atmosphere of freedom, Vangelis brought an acrobat to the studio one night. “I’d never seen anything like it,” Koulouris recalls. “The girl was like rubber!”

During breaks, the band embraced the rock lifestyle. “Paris was beautiful then,” says Koulouris. “We met people, flirted… Some clubs were like theaters where we’d listen to bands like Magma. We wore fur coats and snakeskin boots with twelve-centimeter heels.” When asked if drugs were common, he replies, “Yes. But none of us got mixed up with that. A couple of times, we got ‘pinched’ on the street for not having documents. They’d take us to the station, but someone known would usually get us out. The real problem was the financial. I stayed at Vangelis’ place, and the only chance to eat something decent was when his father, Mr. Odysseas, would send money. Living in a good neighborhood, I’d wake up early, go out on the streets, and if I saw five or six bottles of milk outside any door, I’d take one, add sugar, and drink it. Meanwhile, the album progressed, but you couldn’t tell where it started or ended... Chaos! One night, Irene Papas came and cried out. Then Harris Chalkitis, whom we recently lost, was playing the saxophone ‘ta-ta-ta-ta...’”

Despite having a vision and a plan, Papathanassiou encouraged the musicians to play freely. “Everything I played on the album came from my imagination,” Koulouris says. “We didn’t have sheet music. I remember scratching the strings or putting my keys on them to get a strong electric sound… Today, we can review it. Back then, we didn’t have time for review. It was natural.”

As the album’s completion approached, Mercury refused to release it. Among other issues, they insisted on removing the track ∞ (Infinity), in which Irene Papas' vocalizations evoke an orgasmic experience. Vangelis refused any changes. Months passed, 666 sat in a drawer, and no one knew its fate. By late 1971, the band, showing a sense of humor even in this desperate phase, threw a party at the studio to mark the one-year anniversary of the album's non-release. Among the guests was Salvador Dalí, who was fascinated by the album and soon after proposed an idea for its premiere. He envisioned a happening at the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, with only a single shepherding couple as the audience, who would orally recount what they witnessed to others. Loudspeakers would play the album at high volume for 24 hours, in streets occupied by soldiers dressed in Nazi uniforms. The sky would be filled with military airplanes, which at noon would bomb Sagrada Familia with elephants, hippos, whales, and bishops holding umbrellas. The idea was never realised. When the album was finally released in 1972, Aphrodite’s Child had already been dissolved.

"Everything went fine."

Talking with Argyris Koulouris, we jump from one topic to another. He tells me about his father, who passed away early, the nights he slept with his guitar in his arms, the delicious bean soup he had for lunch, and the evening in Athens when he filled in last minute for a sick musician in James Brown's band. “At one point, Eric Clapton came to the Juniors, and I showed him a few things... He never really impressed me as a guitarist. All those guys became famous because they lived abroad, you know? My little brother used to say, ‘Come on, let’s go to America, I’ll take you around.’ No, I didn’t want to. I stayed with Vangelis, my best friend, and everything went just fine. Our lives were good. Our lives were beautiful. I hope other young people get to experience the magic of music, to listen to what they create in fifty years and feel proud.” Sideras is more reserved. “Yes, I play it,” he tells me when I ask if he listens to 666 today. “I like it. It’s moving overall.”

Now he can enjoy it with significantly improved sound. The new remaster was handled by French sound engineer Philippe Colonna, Vangelis’ close collaborator for over 35 years, who worked closely with him and under his direct supervision in 2021. “We wanted to create the ultimate, definitive edition,” he explains. “We put a lot of emphasis on it because today’s technology allows for sound enhancement and ‘embellishment.’ We focused especially on the first side to highlight the energy of songs like Loud Loud Loud and The Four Horsemen.” The latter is the album's big hit, a great rock track that’s still played in bars around the world and easily stands alongside the great masterpieces of the '70s.

But there are other gems here too. The atmosphere of Aegian Sea, which speakes with Pink Floyd in real-time, the attempts to blend tradition and modernity in The Lamb (which were even more fleshed out in Odes in 1979), and the Eastern/Byzantine flavor over rock orchestrations, all show that Vangelis Papathanassiou was not merely a follower of trends of the time but a voice of consciousness, broadening our understanding of music. The soundtracks he later composed, for films like Blade Runner and Chariots of Fire, would take his music worldwide. The starting point of this journey is 666.

"Did you make this?"

In my university years, I remember arguing with friends whether 666 should be considered one of the most important Greek albums, given that it was recorded under a “foreign” label. Personally, I found it too cerebral. “You have to listen from the beginning to the end, or you miss the point,” musician and songwriter Kyrillos Roussos, son of Demis, tells me. He recalls the first time he listened to the whole album: “I was blown away. When it was over, I went to my father and asked, ‘Did you make this?’ (laughs). Generally, album concepts are tricky. They don’t fit within common ideas of what an album should be. This was a group of young people in a foreign country, saying, ‘Let’s do something crazy, something that’s never been done before.’”

The album lasts 78 minutes. Just when you think it’s over, it throws in a 19-minute jam session. “It definitely has its moments,” writes an AllMusic.com contributor, “but it’s a struggle to listen to all at once.” I mention this to Kyrillos, mostly to provoke him. “And The Godfather Part II is long,” he says. “You need to go to the bathroom before starting it.” A new full-page feature on 666 in UNCUT magazine, coinciding with the reissue, states that “the more you think you understand it, the less sense it makes.” Ultimately, it’s an album that defies control. Its chaos is part of its charm. “An album like this couldn’t even be released today,” Kyrillos tells me, emphasizing the word “released.” “What are we talking about? For TikTok? Where you have to grab the listener in two seconds? How many kids do you think have the patience to listen to an entire song today?”

Vangelis and Demis

What has always impressed me about Vangelis Papathanassiou, aside from his music, is his playful gaze. “Genius and childlike nature usually go hand in hand,” Kyrillos reminds me, having met him as a child. When I send to my brother that old interview from ERT1, with Papathanassiou in a creative estrus, I mostly send it to laugh. But my brother makes me see it differently: “He was amazing—I’ve never seen anyone get such pleasure from his work.” I ask Philippe Colonna what it was like working with him: “He was different from any other musician I’ve ever known. He’d only come to the studio when he was in the mood. He had an artistic approach to technology, aiming to support the creative process. He also paid a lot of attention to his team, making sure everyone felt comfortable. I relearned everything with him.”

And Demis Roussos? I pull up the video clip for The Four Horsemen. Always unkempt, Demis sings, mingles with musicians, licks his fingers while eating hungrily, clinks glasses, and adjusts the channels on a sound console, as if all these were one and the same. It’s as if his artistic expression, life, and rock music formed a unified arena for defending his uniqueness—or perhaps the uniqueness of all of us. When I was a kid, before I could even recognise his voice in songs, I knew about his kaftans. “First of all, we’re talking about a different era, the 1970s,” Kyrillos grounds me as he talks about his father’s solo career. “You had to promote a Greek artist, who was both large in size and hairy, to an English-speaking audience. Artists, media, and record labels worked together to craft an image. And that image sold records.” Did he ever feel embarrassed as a teenager by his father’s cartoonish portrayal? “When I was a teenager, my father wore suits. And there was no internet to see old video clips. Today, when I see old photos, I see a fashion icon. The kaftans and boots were a statement.” Kyrillos is right. You can even see traces of his father’s bold eccentricity in later Greek singers, such as Jimis Panousis, P.E. Dimitriadis, and Konstantinos Konios of the Lungs.

When I finally finish my research, interviews, and reflections, I play 666 once more. It still speaks more to my mind than my heart. Yet, at the same time, I admire the playing, the sound, the freedom, and the madness of these kids who emigrated during the Greek junta—not to create conventional rock hits but to leave behind a record that would remind us forever that there are no limits in art. “Each time I listen to it, I discover something new,” Kyrillos tells me before we close. “Of course, it’s not the album you’ll play every day on your way to work. You have to sit at home, put on your headphones—or if you’re old-school, use your speakers—pour yourself a drink, light a cigarette, and enjoy it in peace. Have a good trip, man!”

Interview by Vyronas Kritzas. Published in K Magazine, October 27, 2024