Interview in American Film magazine, September 1982.

Scoring with Synthesizers

Film composers Giorgio Moroder and Vangelis have heard the sound of the future, and it comes from a machine.

What goes eek, squonk, oing-boing, and waaah-oooom, and has won two Academy Awards in the last four years? Clue: It's neither Jamie Lee Curtis nor R2D2 - though the second is closer.

Give up? The answer is synthesizer movie scores, and the Oscar winners for best score were last year's Chariots of Fire by Vangelis and 1978's Midnight Express by Giorgio Moroder. In both, the music was provided not by an orchestra but by an electronic instrument long used by rock bands. Electronic scores are still relatively rare. But some critics, weary of classical and jazz-oriented scores, welcome them and predict that by the end of the decade. synthesizers will provide the music for most movies. Others, instead, regard the music as a fad. likely to exhaust its potential - and moviegoers' cars - well before decade's end.

The synthesizer debate is succinctly summarized in Jerzy Kosinski's latest novel. Pinball. Rock star Jimmy Osten defends the synthesizer, writes Kosinski. as being not just another specialized musical instrument, but a creative multi-use musical erector set, and he quoted Stravinsky, who had once said the most nearly perfect musical machine was a Stradivarius or an electronic synthesizer. Osten then speculated that the instrument would be a boon to composers and performers; at the merest touch of a button, they could hear full arrangements, as well as endless variations on a single theme; they could compress or extend a phrase, slow it down or speed it up. All this seemed to him an invaluable enrichment of the musical tradition - as well as a means of transcending it.

But Osten's girl friend, a classical pianist, disagrees. For all its presets, custom voice ensembles, special effects, and computerized rhythm and sequence programmers, she says, a synthesizer is nothing but a hybrid of a jukebox and a pinball machine.

Actually, the synthesizer is a bit more complicated than that. Essentially, it's a musical computer played both with a keyboard that allows a pianolike performance and with a series of knobs and buttons that permit all sorts of variation in pitch, tone. and decay. It suggests electricity turned into music. The synthesizer can imitate a large number of other instruments - and still add its own distinct personality. But it can also make sounds all its own. In particular: pulsating beats that seem to echo the human heart; low, buzzing sounds that for bone-shaking vibrations beat conventional instruments like the bass viola; and high, screechy tones rivaled only by the upper registers of violins. Some of the synthesizer's effects can be duplicated by the electric guitar and other instruments, but none has the same range or flexibility.

In a master's hands, a synthesizer can produce memorable film scores, like those for Sorcerer and Thief by the German band Tangerine Dream and for Midnight Express, American Gigolo, Foxes, and Cat People by Giorgio Moroder. But the highest kudos has gone lo the synth track of Chariots of Fire, an unlikely candidate for an electronic score.

Vangelis hit it dead center with Chariots, says Newsweek critic Jack Kroll. It wasn't period but it worked. There was a universality to the score - and it starts right away. That first shot when they're running on the beach - the music tells you what's going on. There's a deep, subliminal suggestiveness. Kroll is also high on Moroder's Cat People score. Essentially, Chariots had a fairly conventional score, mostly a pretty typical keyboard sound. What Moroder does with a synthesizer is very different and much more interesting.

The score for Cat People shows what the synthesizer can do that other procedures cannot so easily do. There's a suggestion that you're listening in on the vital processes of other organisms - of other places, other worlds.

The synthesizer sound has turned out to be a terrific thing, declares Los Angeles pop music critic Robert Hilburn. Midnight Express really displayed its potential. in Thief the music was so strong that it was hard for the director to keep pace with the dynamics of the score in a couple of scenes. In American Gigolo the sensual, decadent quality was especially well conveyed by Moroder's music. To Hilburn, a synthesizer score can heighten the drama. The synthesizer is usually used to build tension with, of course, the big exception being Chariots of Fire. The synthesizer is starker, punchier, and fresher than conventional instruments right now. It pulls you into the scene like nothing else.

But Hilburn and others worry that moviegoers may be in for a surfeit of synthesizer sounds. It's going to be tempting, says Hilburn, to use a synthesizer every time someone does a dramatic film. But, he adds. you can't keep putting the same synthesizer sound behind every nerveracking scene. Besides, even Moroder may run out of ideas.

New York Times critic Janet Maslin observes, Already you can hear synthesizer effects too much in horror movies, where they capitalize on those sounds and repeat them over and over without developing them. That nervous-pulse synthesizer sound is just numbing after a while. And to Maslin, the synthesizer sound has built-in limitations. The synthesizer can certainly add an ominous quality that is hard to create any other way. But when it's used in a more general way. as in Chariots of Fire, it's a little cold, a little impersonal.

Kroll, too, has reservations.It's surprising that it took as long as it did for there to be synthesizer scores, he says. but we may get sick of them. The critics aren't alone. Even synthesizer-sympathetic film-makers worry about overuse. There's a very great danger. says David Puttnam, who produced Chariots and coproduced Midnight Express. It would be very sad if that happened. Nevertheless, more and more producers are using synthesizer scores, and some are turning, naturally, to the rock music world. Death Wish II, for example, was scored by Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, who employed a good deal of both electric guitar and synthesizer; Nighlhawks by Keith Emerson, who, as keyboardist for Emerson. Lake & Palmer, pioneered the use of the synthesizer in live rock shows; and The Long Good Friday by Francis Monkman, keyboardist and composer for the early seventies British band Curved Air.

Before Robert Moog developed his Moog synthesizer in 1964, various electronic noise machines existed, but none with such sophisticated capabilities. The Moog's powers were first fully demonstrated in Switched On Bach, the Walter (later Wendy) Carlos album issued in 1968 that became the biggest classical-music seller of all time. Carlos's classical rearrangements for synth played a memorable role in Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971). And rock scores for synth go back at least to 1970, when Pink Floyd songs were heard in Antonioni's Zabriskie Point.

The synth sound increased in the seventies - both for rock bands and for movies. It's heard, in varying degrees, in The Exorcist (where William Friedkin used portions of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells album), Tommy, Lisztomania (with mullikeyboard interpretations of Liszt by Yes's Rick Wakeman), Quadrophenia, Stardust. The Secret Life of Plants (a little-seen Stevie Wonder-scored work), White Rock (a 1976 documentary that was the official film of the XII Winter Olympics - Wake-man again), and disco-scored movies like Saturday Night Fever, Thank God It's Friday, and looking for Mr. Goodbar.

However, it was with Midnight Express that the synthesizer came into its own. Moroder, as it happened, was not producer Puttnam's first choice. He wanted the English rock band Electric Light Orchestra, but negotiations broke down. Then we heard some things that Vangelis had done, Puttnam recalls. We collected all his albums together and actually cut the film to existing Vangelis material but contractual problems arose. Puttnam and director Alan Parker, stuck for a score, turned for help to Neil Bogart. then head of Casablanca Records. Bogart, who had brought Euro-disco to American prominence by signing Donna Summer, recommended Moroder, the producer of Summer's synthesizer-backed hit I Feel Love.

Alan went to Munich to meet with Giorgio, continues Puttnam, and played him the last cut of the film with the Vangelis material on it. Giorgio developed his own score in about a month. He called when he had the main theme done. None of us could make it to Munich just then, so we listened to it over the phone Later Alan and the editor went to Munich and worked with Giorgio for about a week, and that was it. It was the first rock-oriented score to ever win an Academy Award for Best Original Score.

However, Puttnam adds, I'm not trying to diminish the unquestionable quality of Giorgio's score, but I'm quite convinced that we won the Academy Award because there was absolute hysteria the year before when Saturday Night Fever didn't even get nominated for its score. Too many questions were asked of the Academy's attitude toward modern music. So, to an extent, Giorgio had the Bee Gees to thank for that.

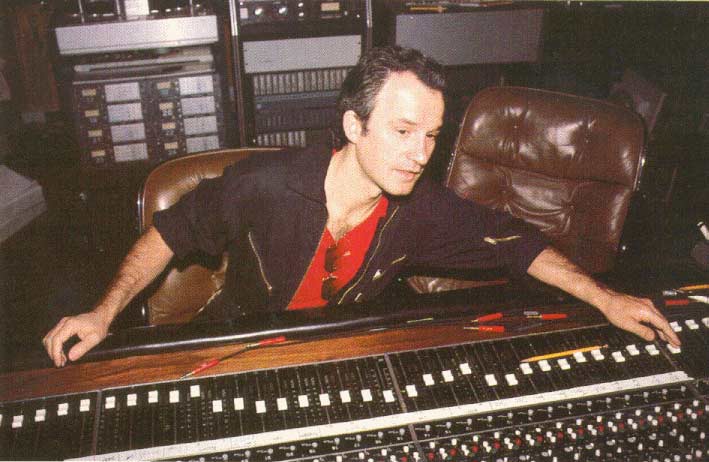

Giorgio Moroder reaches for the right note on his synthesizer keyboard. (sic)

Born in northern Italy. Giorgio Moroder got into music as a bass player. By the late sixties, he had settled in Munich, producing records with his partner, lyricist Pete Bellotte. Influenced by all the synthesizer pioneers around him - Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Pupol Vuh - Moroder eventually started putting the pulsations of the instrument behind the voice of' young disco singer Donna Summer. Then came the worldwide success of Midnight Express, followed by a couple of solo albums - and more film work: a song-oriented score for Puttnam's Foxes (including the Donna Summer hit On the Radio), as well as the scores for American Gigolo (Blondie's hit Call Me was the basis for the sound track) and Cat People.

Recalling Gigolo, director Paul Schrader says, The idea of that film was to have the visual style of Milan and the musical sensibility of Munich. Even though it was set in Southern California, I wanted it to have the look and feel of northern Italy and a brutal, metallic sound. In terms of people coming out of Germany at that time. Giorgio was the most commercially oriented, unlike Kraftwerk and others. He works very quickly and he's very easy to work with.

These days Moroder, who is thirty-six, is far from both northern Italy and Munich, but the synthesizer still occupies his life. Looking sleek and tan in aviator-frame glasses and white tennis shirt and shorts, Moroder sits on a white sofa in his white-walled house overlooking Los Angeles and announces that he, too, is skeptical about the electronic instrument that brought him fame. In fact. a couple of years ago, he says, he was determined to avoid synthesizers on his next film score and compose for a conventional orchestra. But that next film - Cat People - simply growled for a synthesizer sound track. Nevertheless. there are synth sounds that Moroder will not contemplate.

I hate those sounds which are typical synthesizer - all that oing-boing that a lot of rock bands use, he says. It's especially harmful to a score. You have to balance the sound so that it's not too much like an obvious synthesizer and not too much like just another instrument. It should be un-exaggerated, subtle, and as natural as possible. We spend a lot of time getting that right, adjusting the knobs. But don't ask him how the knobs work. I don't know about that technical stuff. I know there are some knobs that give me more highs or less decay, but I'm no good at describing them. I'd rather not know. I just listen to it.

But Moroder knows what he wants, though he seldom plays keyboards himself. I'm not a very good keyboard player, he admits. Instead, he works closely with other musicians, mainly keyboardist Sylvester Levay and percussionist Keith Forsey. With synthesizers, anyway. he says. you have sequencers, so you just push a button. He chuckles. I can do that. Moroder believes that an influx of synthesizer film scores will probably take a while, if it happens at all. That's because, he says, there's a tendency on the part of producers to go for eight or nine big, established composers, who all use orchestra. They include John Williams (who scored E.T.), Ennio Morricone (The Thing), and Maurice Jarre (Firefox), and it explains why the synth sound was largely missing from the summer's big-budget, sci-fi oriented films. Two exceptions were Blade Runner, scored by Vangelis, and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, scored by James Horner, who mobilized an eighty-eight-piece orchestra that included four synthesizers.

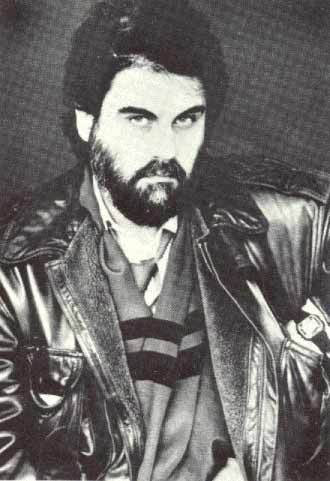

There's nothing wrong with the sound of a synthesizer, says Vangelis, any more than there's something wrong with a violin. What's wrong is to hear any instrument played badly.

Vangelis would do his scores over.

Unlike Moroder, Vangelis plays his own keyboards. I work straight onto the keyboard, the bearded thirty-nine-year-old composer explains from his home in London. And when I have what I want, I can record it directly on tape. My score is my tape.

Even before Chariots of Fire, his first film assignment, Vangelis's music was a staple of television commercials and of shows like PBS's Cosmos, which used extracts from the several albums he had recorded. On those albums he plays all instruments - often several synthesizers and percussive instruments, including a grand piano. Vangelis. who was born in Greece - his full name is Evangelos Papathanassiou - worked with two European techno-rock bands. Formynx and Aphrodite's Child, before launching his solo career.

Even after three film scores (including Missing), he's still a little baffled by the world of film. The pressures of a big-budget movie, he says. are especially challenging, worrying, and exhausting. But you do the best you can in the time given. Still, whatever I do I can always think of doing in a different way. Given more time, I'd like to do things over.

Even some of Chariots? Maybe the whole thing. But then Vangelis laughs and says, No, really I'm quite pleased with that. It was my biggest challenge, being a period film. I didn't want to do period music. I tried to compose a score which was contemporary and still compatible with the time of the film. But I also didn't want to go for a completely electronic sound. That was my main difficulty: how to accomplish that. He accomplished that by mixing synthesizer and grand piano.

Vangelis works in self-imposed isolation, avoiding the influence of others. He has, for instance, yet to see any of the films scored by Moroder - not even Midnight Express. I don't try to shape my career or my music by following what other musicians do. I don't try to avoid all those things on purpose I really must get around to seeing Midnight Express - but I'm very busy in the studio all day. So when I come home at night I'd usually rather do some painting or fool around with some sounds than go to the movies.

He doesn't share Moroder's reservations about typical synthesizer sounds. There's nothing wrong with the sound of a synthesizer any more than there's something wrong with a trumpet or violin. What's wrong is to hear any instrument played badly. Of course, there are people who use the synthesizer in ways that make it sound silly. But that's the fault of the player. Nor has he tired of using the instrument, though he also likes to play others, like the grand piano. I like changing from one to another - each has its own sound and adds its own color. The synthesizer is an extension in musical history the way automobiles were an extension in transportation history. It's a very flexible instrument, and there's nothing faster for scoring a film.

This is one reason that synthesizer composers, working swiftly with dials and buttons and tapes, are increasingly attractive to producers. That synthesizers may indeed be the shape of things to come is ironically illustrated by Moroder's latest project. He is working on it in his small home studio that somehow accommodates not only six of the computer-hearted machines - including the aptly named Jupiter-8 and Prophet 5 - but also the amplifiers, recorders, and other support equipment. The composer sits at an impossibly complex looking twenty-four-track control board, where he gives instructions to his keyboardist, Sylvester Levay, who stands with fingers ready on the keys of the Synclavier II.

Moroder's eyes are fixed on the video screen before him. There's the image of a worker in a great mechanized city of the future operating a huge clock-like machine. But the worker is unable to keep up and collapses as he vows, I will stay at the machine. Another man takes his place, desperately trying to keep up with the machine's demands.

Fifty-six years after it was made, Metropolis, Fritz Lang's dark vision of the future, is finally getting a most suitable score - from an electronic machine.

Interview by Terry Atkinson