Interview in Guitare & Claviers magazine, no 37, January 1984

Vangelis analyses his syntheses

Without Bach, the organ would not be nothing, without Chopin, the piano would barely mean anything, without Vangelis, where would the synthesizer be? An interview from London in his new studio.

Q: Your new studio, is it in fact the old one renovated?

A: Yes. I only made some well-known improvements to it.

Q: When you settled in London at the beginning, you immediately found the studio you wanted?

A: It was the only thing I had decided upon! I started out by making it soundproof, which took six months! But now I can work when I want to and the way I want to. Every day, all the time. Especially all the time. I stay in the studio until two or three in the morning. When I lock myself away, I don't have any notion of time anymore. Anyway, I don't like working in the morning.

Q: With a sound engineer?

A: Yes, we are only with the two of us. But sometimes I would like working with someone more to have a little bit of company.

Q: You make use of synthesizers in a very personal way, in contrast to certain bands one has the impression that you compose for an orchestra.

A: It depends: for certain compositions, I use synthesizers as I would use a symphony orchestra. Admittedly, one cannot reproduce a whole symphony orchestra with a simple box of microprocessors, it misses the human parameter, which cannot be coded. But the principle remains the same. With an orchestra, one uses groups of sounds and one mixes them. And this "mess" of sounds makes up the symphony orchestra.

Q: As a young amateur pianist, you were already considering such compositions?

A: I heard them in my head. More and more, the instruments are able to realise what you feel; and you can set up the things you feel, that you hear. There are two ways of listening: internal and external. Look at Beethoven!

Q: Was it difficult to adapt to electronics?

A: I was never impressed by the synthesizer, and one should especially not identify with it, if not to become enslaved by the technology. I am a kind of automatic pilot: I know the principles, but what interests me is how to operate my instrument. The mathematics of it drive me mad. What's in the belly of a synth doesn't interest me. Having said that, I find that the modern synthesizers are better in terms of sound, but much more complex with respect to the individual. A human being is very fast. Creation is a very vulnerable thing, very fragile. You don't have a second to lose, else it's lost.

Q: Do you keep all your recordings?

A: As a first principle, I keep everything. Afterwards, I listen to it and sort it out.

Q: Were you born into a family of musicians?

A: At home, there was always a piano. That always attracted me. I started when I was four years old. But the sound of the piano was not enough for me. It's an instrument which I adore but has its limits nonetheless. I needed to discover other fields, other universes. So I put up with whatever existed at the time.

Q: With regards to the piano, you are self-taught?

A: Yes, I never wanted to be a concert-pianist. Furthermore, I only learned the stuff that interested me.

Q: As a child, you already wanted to be a musician?

A: I did not know what that meant as a profession.

Q: You were already inventing things at the time?

A: Yes, that's what interested me. At the time, I put nails, plenty of tricks in the piano to obtain different sounds.

Q: Musically, what attracted you?

A: Folk and traditional music, but especially the sounds of nature. At the age of 12, I was very attracted by jazz, and I played that for about the next ten years.

Q: Professionally?

A: Initially I played for myself, but I did form a band with other students to buy instruments, accessories...

Q: So it's your love of sounds which pushed you towards the organ?

A: Yes, very early on, I bought myself a small tape recorder and I started to do the "bread'n'butter" stuff, not to say really conventional. The organ was the only thing that existed at the time. When synthesizers came around, I abandoned the organ. What's hell about synthesizers, is that it's an eternal evolution: one cannot concentrate on the essentials anymore. The manufacturers always try to add gadgets. I believe that the major portion of synthesizers currently around will disappear to be succeeded by a final instrument, according to an evolution close to that of the piano.

Q: How did you discover rock'n'roll?

A: It was everywhere, one could not avoid it! It was a social movement, especially. It all comes from black music, from jazz with a little white thrown in.

Q: Isn't there a contradiction between your great knowledge, like that of a contemporary classical musician and your love of rhythm, soul music?

A: I find that normal. Music is indivisible. One cannot say that "this" music is better than "that". Traditionalists think rock'n'roll is crap and vice-versa. Such idiocy. It's all music. I like to immerse myself in all the sounds, all the possibilities, all the universes. Music always formed part of movements, it got transformed by certain ways of doing things. Music is too beautiful, too much a whole to be divided.

Q: What is your relationship with the public?

A: People like it or don't, follow what I do or don't. If during my life what I do corresponds to the tastes of people, there will be an immediate exchange: it's a fantastic situation, I like so much to share!

Q: When you make an album which has a certain success, its follow-up does not necessarily go down that same route, contrary to the Rolling Stones for example, whose fans buy all their records, systematically...

A: It is true that I have a more diffuse relationship with the public, but I make what I like, as I've always done. When I make an album, it is not to sell it tomorrow. I can compose something today and share it with people ten years later. One should not reason in terms of the hit parade. I always thought so. And if an album did take off, I didn't do anything special to make that happen.

Q: Does it touch you, that people use your music again in other arrangements?

A: That amuses me a lot, it makes me laugh.

Q: Would you like people to play your music a century from now?

A: I never thought of that. That said, what would it mean to me? To please my ego? Not interesting, I already assisted with concerts where musicians played my music in exact fashion, and I was rather impressed.

Q: When you see events like Rick Wakeman who will be playing China, or Jean-Michel Jarre in Trocadéro, don't you want to do something similar?

A: Only "hypes" count for the One in the newspapers. It's a way of working which doesn't interest me. But to play in the street, that's brilliant.

Q: Would you like to return to touring?

A: I will return if I can work "cool", quietly. To have the pleasure of being with people and playing.

Q: And how were those tours with Aphrodite's Child?

A: Disastrous, I hate all that, show business. But at the time, this was all we wanted, it wasn't like an apprenticeship, it was to get across the wall of sound.

Q: During the making of "666", did you have the impression that the others were going to follow you?

A: I hoped so, but didn't count on it too much. It was the end of the band. They were on tour while I finished the demos. It was a different project. We made hits for two years.

Q: Was this the goal of the group from the beginning?

A: No. We rather wanted to make things like 666, but that wasn't possible, especially in France.

Q: Were you disappointed by the other musicians, or was the technology good enough to have given you the means of playing alone?

A: During absolute creation, it is necessary to be alone. A band is formed because one wants to be with certain people, but that does not last very long. I cannot understand people who remain together for reasons of business. It is a very limited mode of expression, valid from time to time.

Q: You are regarded as a rock'n'roll musician. However, your music is not rock'n'roll... What are your thoughts on that?

A: It is necessary to be realistic: showbiz people find you brilliant if you're selling, if you don't, you're broke. They are there to make money, but that drives me insane. One always complains about the record-companies, but the musicians are often worse! In fact, there are faults on both sides.

Q: When Aphrodite broke up, with "666" not taking off as wished for and then the record-company

didn't support you anymore, how did you get through this period?

A: At the time, I was a little saddened by this lack of communication, especially with the record-company. They didn't understand a thing. They lost out on an opportunity. But they didn't hurt me, I did not really need them. The moment you have the essence, the vitality, the money, you can move on.

Q: You were not afraid when you noticed that after one, two albums, people didn't follow you?

A: I don't let myself depend on what I'm selling. If people like it, so much the better, but if not, I make what interests me. I do not want to attack people; I give few interviews, I do not make publicity. People are not idiots, they're well able to know what they like by themselves. Having said that, after the Aphrodite period and the hits, I felt free: I didn't have to return any favours anymore, I wasn't pushed anymore into making success after success. So it was a relief especially.

Q: You've always designed your albums as distinct entities...

A: When I'm recording, it is not to make an album. I make music, all the time. Furthermore, I try not to become a product. It's not because a record took off that the same thing should be made again, it's necessary to escape from these repercussions of success. If I were reasoning in terms of business, I might as well stop today: I have the material to make records for a hundred years!

Q: Your albums are not a simple succession of pieces, there is always quite a particular direction...

A: That's my problem when I make a record. One can never say that a recording is definitively finished.

Q: Nevertheless you've made albums based on concepts, like "Beaubourg" or "China".

A: Yes, but the name does not carry any importance. I am not in the position of a singer who makes his "latest album" and goes on tour until the next one. I have music in reserve some of which perhaps I will use in twenty years time. Therefore, a record that's just come out inevitably does not exactly represent my work at this moment in time.

Q: The public often has the impression that there are three Vangelis personae: you, film-music and finally the albums you make with Jon Anderson.

A: What's important, is the character, the style of the music. You speak about three Vangelis, but there are perhaps twenty. It is that which is beautiful.

Q: Film music is something that appears naturally to you: even the albums which are not designed to accompany a film are often used to back up images...

A: True. What is incredible, is that when I compose, I don't see any image. Music is organic, one does not invent anything. It is not my music, it is the music in which I swim. I am a kind of receiver.

Q: When you write the music for a film, you watch the images in order to compose, which reverses your creative process...

A: Yes, because in a film there is a problem called "timing" which calls for a very high degree of accuracy. But where I can make up ground, is that I translate the images into different entities, into energy, into volume, into music. Anything that functions similarly, tastes, colours, the relationship between things. But I only make film-music because it changes me, I do not make a specialty of it.

Q: You also refuse to release certain music on albums, for example that of Missing.

A: I always avoid making the same thing, to benefit from a favourable situation. It's not my job, I am there to compose, that's all. It's always the same problem between business and creation. It is necessary to be conscious of what one makes to limit the risks, never to regret it. That reduces the problems between a record-company and the musicians.

Q: In France they've succeeded in getting the album of Antarctica, but they will probably never see the film, or at least not for a long time...

A: Maybe, who knows. But the film took off so well in Japan that it will surely get here.

Q: What's the story?

A: It's a story based on facts. At the end of the Fifties, scientists left for Antarctica to explore it. To move across the snow, they took along dogs and a storm forced them to give up. At the end, one sees the whole life of the dogs in the snow. It's a tale about men and animals that very much characterised the Japanese which perhaps explains the success of the film over there.

Q: Would you like to create images yourself?

A: Yes, certainly, if I can be my own patron. I don't want to be a prisoner of material contingencies. I want to control everything to be able to save my heart!

Q: And to make music videos, does that interest you?

A: Yes, but not in the way currently in vogue, which is to make videos for the promotion of records.

Q: Let us speak about the other aspect of your career, that with Jon Anderson.

A: I met Yes at the time of a concert at the Sports Stadium in 1974. We immediately had good contact, we became friendly. I was never crazy about the music of Yes. With Jon, we wanted to do something together which was done naturally, without any commercial idea.

Q: When Rick Wakeman had left Yes, they spoke about you as a substitute.

A: Yes, because Jon proposed it to me. But I refused, I did not want to play in a band. To please him, I went to London. But it didn't go well, the fact that I didn't like it didn't change anything between us.

Q: What does it bring you working with him?

A: It enables me to be in touch with other fields, to change a little. For example, the first album was made one weekend when we wanted to play and sing, in four days. There were no second takes, everything was done live.

Q: Does that mean that you did all the rhythms, on which you work?

A: I have keyboards all around me and I played them all at the same time. He was singing. The majority of the lyrics were created at this time, during the take. The complete recording took ten days. The second album was made similarly. We improvised for two days, then I mixed all the tapes. We made it to get the good moments on record. It's difficult to believe, but that's all there is to it really. I worked with Jon for the change, but also because things are natural between us. If we'd had to prepare the albums, that wouldn't have interested me. The unknown, that was good. One minute before starting the recording, one did not know what one was going to do!

Q: That's what provided the title for the "Private Collection" album?

A: No, it's just a title. But it's true it was a private thing, without publicity...

Q: On "Back to School", you can well recognise all the fun you had doing it...

A: Yes, it was spontaneous. If this spontaneity is broken, the record is gone.

Q: On "Private Collection", Polonaise seems to me to be slightly off-topic...

A: It was at the time of the Polish problems. One cannot escape from what surrounds us. It is not political, it's human, we are touched by this event.

Q: Which musicians are the ones that impress you?

A: It is they who are in touch with nature. When you agree with nature you obtain, no matter in what style, something impressive.

Q: When you sense that you're playing something exceptional, do you feel "something's coming"?

A: Yes, and that enables me to precisely carry out what I feel. It's a little odd, one does not know exactly what occurs. There is a serenity, a great tiredness, a nervousness which invades you: these are the symptoms. It's all biological. And when I hear some music which I feel to be "forced", that gets me really sick.

Q: How do you place yourself with respect to other musicians whom one classifies along with you as "keyboard nerds", as in a demonstration of technology with plenty of hardware?

A: It is difficult to speak about the others. They all have their own conscience... I can say most of the time I regret the lack of feedback, of contact with the instrument. It is like trying to touch a button to make "gloup gloup", but I regret this mechanical, artificial side.

Q: All the new techno-pop groups who use synthesizers, what effect does that have on you?

A: I wait until it passes over! And what remains will perhaps have more purpose.

Q: Already the technology will remain...

A: Yes, but the question remains: does the technology control us or do we control technology? I am against technology becoming in control.

Q: What kind of music do you listen to?

A: It depends on the moment. A little of everything. I am rather curious, I try to find things. Everything is of interest to me. Like I said, music is all one.

Q: Do you listen again to music?

A: Rarely. The interesting point is when I conceive the music, not afterwards. What's important is to do it.

Q: There is a topic about which one seldom speaks regarding your subject: you are a percussionist...

A: That's true, I much like percussion. It is so biological. Rhythm is essential. There is much wisdom in rhythm, it's life itself.

Q: Do you like to use electronic rhythms, sequences, or do you really like to "bang away"?

A: Both are relevant. At times I drum, and sometimes, I get drummed. I cannot live without rhythm.

Interview by Yves Bigot

Transcribed and translated from French by Ivar de Vries

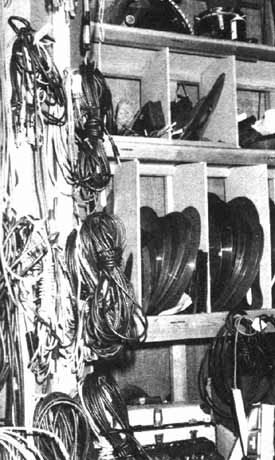

The tour by the landlord

Vangelis does not posses a considerable amount of gear. He prefers by far the quality over quantity. Two electric pianos, a Fender 88 and a Yamaha CP80, are enough for him. He still uses the Linn as a percussion synthesizer, as well as lots of toms, futs, cymbals and a Simmons. For Reverb he uses the echoes from the Lexicon 224. Arp and Roland dominate the generation of sequences. A Roland (Vocoder plus 330) is used for processing of voices. As far as synths are concerned the ex Aphrodite's Child is faithful to the Minimoog. In the mean time he acquired an Emulator 6008, a Prophet 10, a Roland JP4, a Trumars Comphonic and, recently, the Yamaha DX7. Nothing was "given" to him, he refuses and prefers to buy his machinery, like everyone, in the stores.