Interview with Vangelis in Keyboard Review magazine, issued in December 1992.

Natural Man

There can be virtualy no one in the civilised world who hasn't heard the theme from Chariots of Fire. Its Greek-born creator, Vangelis, has explored many aspects of music but always with the need to be true to himself. Malcolm Harrison talks to him about his eclectic career.

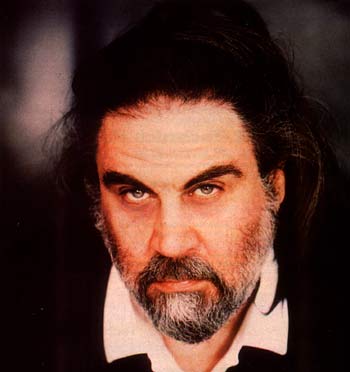

Vangelis likes to play. Not for him the interminable overdubs, computerised accuracy or orchestral authenticity. He wants to play. "I like to be able to perform as quickly as possible what comes into my head and my heart. In my case if I spend so much time with computers, programming track by track, that's a nightmare and I lose the freshness and spontaneity of the moment which is vital for me."

But he admits not everyone thinks like him: "That's not the way it is for other people and not the way for the designers of synthesizers because they do everything to complicate your life. Here I am, the man who loves technology but hates technology because of its design, not for its existence. It's sad." (More of his views on instruments later!)

Vangelis is an affable man; someone who abhors the ego polishing that comes with the music industry. This is someone who'd have made music his life whether he was paid or not. He's a man who because of his almost spiritual approach to life seems to have naively outspoken views on musicians, music, instruments and the business -until you understand his standpoint.

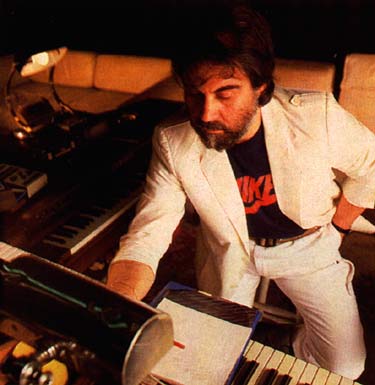

I'm talking to him on a delightful autumn afternoon in his first floor "glasshouse" studio in central Paris. He's surrounded by keyboards, modules, mixers - indeed, he has three separate keyboard set-ups within the studio. He rarely gives interviews so this is an opportunity to talk about life, the universe and everything, especially his latest soundtrack. 1492- Conquest of Paradise, for Ridley Scott's sumptuous film of the same name.

VANGELIS ON...

...FAME

"I know it's nice to be known - It caresses your ego - but the society cost is terrible."

...MOTIVATION

"I was born motivated so I don't need a commission to create something. A commission can create panic more than anything else. The obligation to be successful is anti-creative; creation should be free."

...MUSICIANS

"There are too many musicians, too many painters, too many writers and they're all trying to fit - it's impossible. On the one hand it's fantastic that people spend time with instruments, with writing, with painting; It's very therapeutic but this doesn't necessarily mean everyone has to be number one. The main reason and motivation for many musicians is how to become famous not how to make a living. That's pathetic."

...MUSIC BUSINESS

"Everyone criticises it but no one can do anything about it. You're a prisoner of the system - uncomfortable and unhealthy. The aim is not to create a beautiful piece of music; the aim is to create a piece of music that is able to fit into the system in order to be number one. Try to make a hit and you will never make it. Try to be honest and create something you really enjoy you might have a hit. Can you Imagine the agony and unhappiness and the stress of the people who are going into the studio to create a hit single? You can feel this agony in the track because it's not honest."

...HIT SINGLES

"People don't have much choice because they listen to whatever the media and record companies offer them. Everything is so controlled today. You go into a supermarket and buy whatever is offered to you. Record companies are the same -you buy what they offer you - and then you have to live with it. I don't believe It when they say 'oh, this isn't marketable; people won't buy it'. So many times they've been wrong. Look at the Chariots of fire single. The Americans said 'this piece of music will never sell in America' and it was the record company's first number one in America."

The music is often dark and ominous which, as Vangelis puts it, "goes with the period". He's an instinctive worker in the medium: "I look first, get my first reactions and immediately play. If it had been another moment it would have been another score, another approach - but the same film exactly. But, of course, we can't do two scores for one film..." says the multi-lingual Greek laughing.

This brings us on to the wider world of film scores - a form Vangelis enjoys but about which he has many reservations. "It is a good exercise sometimes: an occasion to work with different people because mainly I'm working by myself spending hours and months alone. Also it is a challenge.

"I think the music is the most important part of a film. But it is an afterthought due to the ignorance and negligence of directors and producers. I'm not talking from the musician's point of view; I'm not biased. Because I see it every day, I believe strongly that music has a fatal power to change the existing situation and image."

He turns to the TV which is on (though soundless) in another comer of the room. "What you see on TV now I can score in 10 different ways and it's going to be the same scene, happy and tragic, melancholic, weird, esoteric. Although producers and directors want and need the music they should be very careful about it. At the beginning when they build the film in their heads -the whole plan - they should really think and feel the type of music they want and maybe work in advance sometimes. I'm not saying that when I'm writing a score I'm right -1 can be wrong - but what is important is to be very careful and do the best you can."

He says most producers and directors don't understand the importance of music to films and therefore it becomes a minus point instead of a plus. "A film can be extraordinary with the right piece of music or with no music at all - it's not always necessary to have music."

It seems to me that Vangelis' strength is the simplicity of his ideas - just take that main theme from Chariots of fire. How do these themes come about? "They happen. When I do something like that I try not to think. It just comes naturally. And why naturally? Because what I see creates an emotion and this emotion comes out immediately," he says with a click of his fingers. "It may be the right one or it may be the wrong one. Usually the first one is the right one, and then the second and third are much more intellectual in approach which is second best. That's why I work in a very quick way. From this set-up," he says embracing the keyboards that surround him, "I can trigger anything I want in a split second. I like that immediacy and playability."

Vangelis doesn't read or write music; however, music seems to have been instinctive for him from any early age. "When I started composing I was nearly four years old so I didn't have any memory of music - it was too early. But I was sitting at the piano and using everything I could find in the house from the percussive point of view. I was spending hours and hours creating sounds or playing whatever was coming into my head. 1 don't remember myself not composing. It wasn't something that came because of certain influences."

He declares a love of all music: "For me it's one thing - just different branches, different directions. I can't say 'this is music and that is not music'. People often make a fundamental mistake when they talk about a type of music they don't like; sometimes it's not because of the form. I like every form of music - what I don't like is the content. Sometimes people say 'this is too modern, too contemporary, I can't understand it'. I don t think this is true concerning the form of music, it's more what's in it."

For Vangelis music is a way of life, not a job or a career. "The only moment I felt music would be a career was when I realised there is no other way to survive and have my own studio, my own instruments and all that. I found myself obliged to get involved with the music industry otherwise I think I would have continued to do exactly the same thing without releasing any music at all. Now I have to release music because I have to make sure that I can pay for all you see around you and people who work here."

It's a responsibility that worries him for two reasons. "Firstly, sometimes you have a commission which you don't feel like doing; second, more and more of the commissions are silly and more people are geared into empty commercialism. One thing I don't understand is why we always detach the commerciality from quality. I think they can be together. I think we do it because we're afraid. We try to be so simple in order to be understood, for people to buy the product. For example, the Eurovision Song Contest, middle-of-the-road music, the top 50 - this is the manufactured part of music and it is very unhealthy."

Many people would counter that by saying that because of his success Vangelis is able to ignore the commercial pressures. But apparently he has insisted on artistic freedom since his very first contract. "I always try to keep a balance between being able to make the necessary money for what I need and to keep my self respect. It's a very difficult balance. It's very tiring as well," he says with a smile.

Vangelis' musical life has contained many elements. He began his first electronic music experimentations in the early 1970s when he moved from his Greek homeland to Paris. His emergence into the public eye coincided with a move to London and the establishment of his Nemo studio. There he created some of his best-known albums: Heaven and Hell, Albedo 0.39, Spiral and China. His first collaboration with actress Irene Papas on new Greek music came in 1979 and a year later he joined forces with Yes vocalist Jon Anderson. In the same year he played with a symphony orchestra in Belgium.

Since then he's gone on to compose music for many major films: Chariots of fire, for which he won an Oscar, Blade Runner, Missing and The Bounty. He's also worked with Jacques Cousteau which has resulted in the music for three of his underwater films.

In 1983 Vangelis composed the music for the Greek tragedy Elektra (featuring Irene Papas). Two years later he worked on the modern ballet Frankenstein - Modern Prometheus performed by the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. His links with Irene Papas were strengthened again earlier this year when she starred in a Spanish production of Medea for which Vangelis wrote the music.

When it comes to discussing the Vangelis armoury of equipment, the man is reticent to detail individual instruments. Indeed, many of the keyboards in his studio have the manufacturer's name blacked out by tape! However, he's willing to talk in general terms; "It's very simple: I use everything you can buy on the market. Why? Because what's going on in musical instruments now is not very inspiring. I don't think synthesizers have developed in the way they should. Nobody in the world can develop and make a better instrument every year. For acoustic instruments it took years and years - centuries - in order to create the instrument. Here we have an instrument that lasts six months then another one comes and you have to learn how to operate that. None of these instruments become easier to play. When I say 'to play' I mean really play because the market is more orientated to people who don't play.

"We create new generations of damn people and we push them away from the only unique asset that human beings have, the means of expression and the freedom that makes us individuals. It's very dangerous that this individuality is threatened by the industry. The young may not feel that but it doesn't mean it isn't dangerous. Here we live in a very polluted place, for example, and although we don't feel anything perhaps in 10 years time we'll have lung problems. It's the same thing."

To emphasise his seriousness, he adds: "This is the most vital part of our discussion. Expression should be helped and amplified not restricted and castrated.

"I don't see instruments for real musicians today. They're second rate. That's one reason why I buy too many because each one can offer me something that another can't -1 take 10 per cent out of each. For example, instead of giving you 10 facilities they give you one or two and then six months later another instrument gives you another facility which should have been on the first one. It's a purely commercial approach."

Vangelis is equally vociferous about the reasons for using a synthesizer. "It doesn't replace acoustic instruments; it can do different things and can extend things. But, of course, during the first years of the synthesizer, they started making silly weird sounds, they played classical music backwards - all that was really marketing. Synthesizers aren't for that; they're to somehow be closer to nature. Although people may think 'closer to nature' means an acoustic instrument, I don't believe that. It's as close to nature as you can be. It doesn't matter what instrument you use. People say synthesizer music is very cold. But that's not the synthesizer; well, it's partly the synthesizer if it's a bad instrument but mainly it's the musician behind it. The difference is that with acoustic instruments the player has the ability to put in this precious thing we call soul. But that's what I'm trying to do with synthesizers.

And because of this approach he's disillusioned with the expressive limitations of today's keyboards. "Once Synclavier said it had the best piano sound in the world but the keyboard wasn't a full piano keyboard. So I said to them 'I don't see how you can play a real piano if the keyboard has less octaves than the real piano'. They said 'you can buy a mother keyboard'. But I said 'If I'm paying 300,000 dollars for this machine why can't you add two octaves to your keyboard?' This kind of conception is very backwards."

He expands in the same vein; "You can have the best samples of flutes, 'cellos and strings in the world but if your keyboard is not good enough to express them they sound worse. With an analogue sound there is no point of reference; this is the sound whether you like it or you don't. But when you have an acoustic sound sampled and your keyboard can't deliver the expression for, say, a violin it becomes a cat. What makes a violin is a violin player, not the violin itself."

I'd heard earlier in the day from technician Frederico Rousseau, that Vangelis never sells any of his instruments. He confirms this. "In one way older synthesizers sound better than new ones. The new ones have some sounds that the old ones didn't but because you don't have the instrument you have to take a little bit of everything. Analogue synthesizers didn't have the pretension to sound like a real string section or brass section and you could change things during the playing. After the DX7 came out it was an evolutionary moment from the sound point of view, but from the technical point of view it was the black moment of the industry. Because of its success everybody started to copy that and things became more and more complicated. On the one hand you go forward and on the other you go backwards."

And he adds with a laugh and a twinkle in his eye: "Also although I don't like all these instruments, the moment I play something it becomes my friend."

A small sample of his hardware reveals Kurzweil K1200 and K2000; Yamaha CS80; Roland D50, JV80, JD800, S770 (two); Korg Tl, 01/W, Wavestation; Akai S1100 (two), DD1000; and Waldorf Microwave.

The studio is split into three set-ups: a 24-track digital, a 24-track analogue and 48-track digital. "Immediately when I play something I can record it. If I want to change something or add a little I can, but most of the time the take is the take."

On the subject of editing, Vangelis returns to a familiar theme: "I'm totally opposed to all these expensive bullshit computers. They can do whatever you want but not in the time you want. I've spoken to many other musicians and something that strikes me is that these people have lost the essence of time. One said to me: "With this new computer I can create something in one or two minutes'. This is an eternity. I can do that in a split second. But the split second doesn't come into account because the previous computer could do it in 10 minutes - so for them, 10 minutes to two minutes is really great progress!"

With his "real time" system Vangelis can create a symphonic piece in the time it takes to play it - half an hour or an hour - but he's not interested in authenticity for authenticity's sake. For example he won't line up four violin voices, two viola sounds and so on to build a synthetic string section. This is because he believes synthesizers don't work in the same way as orchestras.

"They have different characteristics and different harmonics. The accuracy is given by nature and the ear can say immediately 'this sounds right, this sounds wrong' so the amount of each element is being dictated by the natural law of sound. I would never sit down and say 'OK, we need two violas, four violins...'. You can do that when you deal with acoustic instruments because the sound comes from the instrument direct - you have to balance the levels and the colours. Sometimes people write something for synthesizers and then convert it for orchestras. That's wrong. They are different animals.

If you've ever heard Vangelis playing live then you've been very fortunate because he doesn't generally feel the need for this type of exhibitionism. "I just feel weird sometimes when I'm on stage. Why am I doing this? Why are these people looking at me? Maybe I shouldn't be here because I have nothing to sell. You see, when you have something to sell, the concert becomes part of the marketing campaign. Also if you don't feel it's necessary to be loved, applauded and adored by people you feel a little bit weird."

What will tempt Vangelis out of his shell is a cause or something of which he can feel part. Last year he organised a huge event in Holland to celebrate Europe's Eureka project, and he also hosted a gala in Athens as part of the World Society for Poetry, Drama and Literature when he appeared with Alan Bates, Fanny Ardent and soprano Markella Hartziano. However, he does understand that fans would like to see him on stage although he still has reservations.

"I don't like the obligation to be successful. Concerts have to be planned a year ahead sometimes and I don't know how I'm going to feel in a year's lime. If you want to create a successful concert, it's partly due to the organisation and the money spent around you. So I feel responsible because I spend a few thousand pounds or dollars to be a good boy and play well in order to make everyone feel satisfied," he says with a smile. "It is an obligation that puts me off. For me a concert is a real thing, a live thing, an adventure - and the adventure is bigger for me than for the people out there. When I'm on stage I play completely new things. I don't program or prepare anything. It's like a white page: I come on stage and start playing and I don't know what's going to happen. Sometimes it works and sometimes it might not."

Vangelis makes the distinction between concerts and events - the huge open air shows where he will play his "greatest hits". Recalling the event that attracted more than 150,000 people in Holland he says: "There I had to do things that people knew and you have to be linked with a computer because of the lasers and fireworks. That was good to entertain people, and I did it because I thought it would be fun to do it once and see how it works."

As far as forthcoming albums are concerned, Vangelis' other-worldliness resurfaces. "The albums are not something that are up to me; they're up to the record company. The album is a music industry term. For me there is not such a thing as an album; there are just pieces of music. I create music every day because this is how I function. If I stopped playing or composing now and never put my hands on the keyboard again I could have maybe a hundred albums to release. The problem is the industry. The reason for the Columbus release is because we can't release the Polanski film score (Bitter Moon), we can't release the Cousteau film. The record company doesn't want to release these because it can't cope with them all. So if they have to release three soundtracks in one go plus other pieces of music I could have 10 albums a year. I don't know whether that's good or bad but it's not up to me; it's up to the system. But nothing will stop me making music every day."

Interview by Malcolm Harrison, 1992