Interview in Melody Maker, October 2, 1976

Vangelis: Machine Head

Vangelis was preparing for the premiere of his latest album, "Albedo 0.39", which was due to take place at London's Roundhouse on Tuesday this week (now postponed).

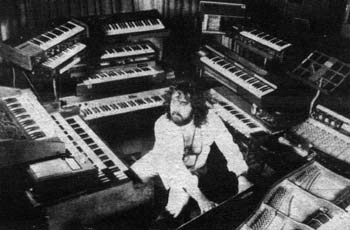

There were keyboards everywhere. Ten, including a grand piano, were arranged round three sides of a square, while the electronic citadel was completed by a 32-track mixer. Which he also operates.

Five more stood in one corner, while two languished beside a stack of speakers and amps. At the other end of the studio lay a Korg Polyphonic Ensemble, dusty, unplugged and forgotten.

To say Gelly is one of the kings of the keyboards is something of an understatement. He shrugs at such a thought.

"I play them because I need them to translate my thoughts into music. If I needed more I would have more. I could get by with one that would be enough."

"I do not use keyboards in great numbers because I think it will impress people or to satisfy an ego trip. It is necessary."

"I sometimes wish I was Oscar Peterson and could just be satisfied with one. He does not even have to take his keyboards with him on tour."

"When he goes to a concert hall a piano is waiting for him but me? Hah! Look at all this, it all has to go to the Roundhouse. Maybe I should take up the flute."

Vangelis, previously a member of Aphrodites' Child with Demis Roussos, went solo in 1968 and spent much of his time writing film scores. Then last year he was signed by RCA and released his first album tor them in November - "Heaven And Hell".

It was an extravagant album, launched amid much brouhaha at an equally extravagant concert at London's Royal Albert Hall, his debut solo gig in Britain.

Of course saying "solo" is rather stretching things. Besides Vangelis and his banks of keyboards and percussion instruments there were also dozens of dancing girls, loads of African drummers and a full-blown choir. There was no way he was going to be lonely.

For some it was excess gone insane. But Vangelis is unrepentant.

He planned for "Albedo" a much lower-key affair. First, he did not intend to do everything himself and roped in a bass-player - Greenslade's Dave Markee - drummer, percussionist and a couple of other keyboard men.

On the album, though, he did everything himself. Keyboards, drums, percussion, bass and other assorted effects. He also composed, arranged, produced and edited it all, with a little help from sound engineer Keith Spencer-Allen. Oh, it was also recorded in Vangelis' own studio near London's Marble Arch.

That's where he was last week, working with two engineers who were trying to organise Vangelis' spreading array of keyboards into some semblance of order and accessibility.

At one time the two were inside the keyboard fortress and Vangelis attempted to join them. He couldn't get in. He even offered to crawl under the grand piano, but they demurred at the thought of him getting tangled in a forest of leads.

One looks at the vast array and asks what exactly Vangelis is going to play in concert. He stares in surprise and then sweeps his arms wide in an expansive gesture. "Whatever you see I play," he says, as if shrugging off this obvious question.

"You see, to have exactly the same thing live as on the record I must have all these instruments. But of course I have other musicians to help me this time."

"I would wish to have three pairs of hands to play it all, as on the record. With one pair I do a lot but it is never enough. Always I want more."

"You see, I feel that the connection between the brain and the body is a complete disaster. The brain is much too fast, it demands more things than your body can supply."

"So there is always dissatisfaction at whatever you achieve. I want more keyboards to express myself but I cannot play them all."

"But it is not meant to be a trick or something. If I was trying to do just that then I would be playing in a circus, not at the Roundhouse. People say it is gimmick, but for me it is not."

"People ask why I play so many keyboards and I say why do you think that a symphony orchestra has to have 100 members? That is what the music takes."

What Vangelis's music takes these days is quite a battery. Around himself he has an Elka-Orla Rhapsody, two ARP Pro-Soloist synthesizers, a Steinway grand, two Roland synthesizers, a Fender Rhodes electric piano, two Korg 700 synthesizers, a Korg Polyphonic Ensemble and a Fartisa Syntorchestra.

In addition, there is the aforementioned 32-channel mixer plus a trio of Moog drums, two echo units and half a dozen effects units.

In the meantime, he has an echo patched in directly to the mixer, plus another with which, at the time; he wasn't quite sure what he was going to do.

For his two assistants on the keyboards at the live "Albedo" he planned two ARP synthesizers, a Hohner Clavinet D6, a Solina String Ensemble, a Mellotron 400 and an EKO Stradivarius String Synthesizer.

It all makes Reginald Dixon and his mighty Wurlitzer look rather silly.

VANGELIS: 'I sometimes wish I was Oscar Peterson and could be satisfied with one keyboard'

But Vangelis is not satisfied, so he says. "I think keyboards are in a primitive state. Like anything else, keyboards are first of all regarded as products."

"The manufacturers see them as something which makes money. And because of this there are too many compromises."

"A maker of a keyboard will try and compromise so that it suits as many people as possible. This is not criticism because everyone must have money to live. Records are released to make money and concerts are done to make money. It is similar."

"But I think keyboards can be expensive for the average person. When you are talking of £400 or £500 this is not something which everyone can afford."

"It has happened in the past that keyboards are made and designed by people who are not first and foremost musically minded. But musicians come to them and suggest changes and so they try to combine the basic idea with what musicians tell them. This is a step in the right way but it is still a compromise."

"No matter, though. It is changing all the time and I think that in the next ten or 15 years synthesizers are going to become as popular as pianos were in the time of Queen Victoria. Then everyone had a piano which was played every day. I think this will be the same for the synthesizer."

"There are two reasons. First, is maybe a silly reason. The synthesizer is smaller than the piano and looks more modern."

"But, secondly, the synthesizer gives you the choice of any kind of sound. Everything is automatic on a good one."

"It can satisfy the architect or the dentist who wants to impress his family and show what a good musician he is. No, seriously. You can play with one finger and you can produce the most amazing sounds."

"It is like the Hammond organ. There you have automatic drums, automatic bass, automatic rhythm and all you play is the melody line with one finger. It is perfect for home use when you only want to enjoy yourself and sound better than you really are."

"Of course, once you play that, you should really drive yourself on to something else - some musicians are still at that stage, but I name nobody. They know who they are, perhaps better than anyone else does."

Vangelis is, one might notice, perhaps slightly bitter to those who he feels take music less seriously than himself. But this is only a passing moment. He rarely concerns himself with the music of others. It is his own imagination which consumes his time and energy.

That is why he is surprised at those who regard the synthesizer as more impresive than the musicians playing it.

"It is wrong to be impressed by the machine. It is the man behind the machine who is providing the driving force. The machine itself does nothing."

"Always remember that when you hear a marvellous sound coming from a synthesizer it is not the machine that is doing it - it is the imagination of the man playing it."

Nonetheless Vangelis is enthusiastic about synthesizers and he also regards the acoustic piano as an unsurpassable instrument.

"When you play a grand piano it is like magic. The tone is impossible to reproduce electronically. It is a singular instrument and a special one."

"While I say that synthesizers will become the most popular instruments for domestic use, and they are already very popular among rock bands, the piano will always remain important."

"On the other hand, the piano is also a very static instrument. You know what it sounds like, you know it can never sound any different. That is where the synthesizer is at its strongest. It was built to incorporate many sounds and possibility of creating new ones."

"That is another point. When synthesizers first become available people used them to reproduce the sound of other instruments."

"Or perhaps they tried to play in a gimmicky manner. But in fact it is up to us, the musicians, to make a synthesizer sound like a synthesizer - an instrument in its own right."

It is unsurprising to find that Vangelis, having said that about synthesizers, is none too enthusiastic about Mellotrons. "It is a personal thought," he says. "They are a dead instrument."

"They are an easy way to have all the sounds of a 40-piece string section. It is all sealed up," he says rapping his can of Diet Pepsi, "like something in a can. Open it and the music pours out. Close it and it stops. There is no life, no magic."

Interview by Brian Harrigan