Interview in Pulse! store music magazine at Tower Records, USA. Issued in September, 2001

Communing with the Gods

A lots of artists can get large orchestras and impressive venues in which to play their music. But how many could compose an opus to Mars and have the planet itself rise above the stage in midperformance, sitting, no less, at its brightest point and closest proximity to Earth? Somehow, Vangelis accomplished that. "I just called Jupiter before the concert and I said Can you arrange for Mars to be in the middle of the stage and quite bright, please,' says the Greek composer a few days later. He does wink, although the fact he thought it necessary says something about how Vangelis thinks he might be perceived.

Vangelis was an early test pilot for space music. Albums from the '70s, such as Albedo 0.39 and Spiral, cruised the starways right alongside Jean-Michel Jarre's Oxygene and Tangerine Dream's Stratosfear. But even though his latest opus, Mythodea (Sony Classical), has been selected as the theme music for NASA's Odyssey mission to Mars, none of the familiar Vangelis landmarks is there. There are no thudding sequencers or solar-flare melodies.

"I don't try to describe space, I'm just working with space. If you describe space, then it's a different thing. It's like science fiction, but space itself is enough to impress us." explains Vangelis.

Vangelis premiered the work eight years ago with no concept of space imagery, yet in the center of Athens, interstellar space is meeting ancient mythology, all for the benefit of a fall PBS performance special. Decayed Corinthian columns rise up on the left side of a stage mounted in ruins of the Temple of Zeus. A scrim that must 300 yards long and five stories high shifts with projections of Greek gods, warriors, icons and images of space and the planets. On stage are 24 timpani drummers, a 100-voice choir and a 70-piece orchestra. And in the middle, buried behind an imposing cockpit suitable for Darth Vader, is Vangelis, the Greek who was synonymous with synthesized music of orchestral grandeur long before Yanni.

Vangelis could be accused of mimicry, following in the footsteps of Yanni, who performed at another Greek landmark, the Herod Atticus Theater at the Acropolis. But as a Greek woman sitting next to me snorted dismissively, "Vangelis played there years ago." He's arguably the best-known musician in Greece; in hotel lobbies and on the fingers of restaurant pianists throughout Athens, you can hear Vangelis' "L'enfant," a theme from the film The Year of Living Dangerously. But becoming Greece's MuzakTM was not what Vangelis had in mind, and therein lies his dilemma.

A '60s pop star in Europe with Aphrodite's Child, he became a progressive rock keyboard god in the 1970s, consorting with Yes and recording with Jon Anderson when that was still a cool thing to do. Soundtracks to Chariots of Fire and Blade Runner launched him to the forefront of film composition, and those very same themes were turned into easy listening and, ultimately, parody. Although he expresses no desire for legitimacy or credibility, it seems that Mythodea, replete with orchestra and operatic super-divas Kathleen Battle and Jessye Norman, is pointing him in that direction.

"I think that Mythodea is classical music," insists its conductor Blake Neely, who isn't exactly a classical purist. His previous work includes Metallica's orchestral S&M and the book Piano for Dummies. "I think that in 10 years, 20 years, people will recognize it as classical. I have long discussions with him about this; he's always wanted to be recognized as a great composer, not a synth composer, not a New Age composer, not a film composer, and this may be the piece that people finally say 'Oh, I get it, you're a composer, no category applied." A few days after the concert, at a resort on the Aegean Sea, Vangelis sits down wearily on a sofa. Dressed for video cameras, he's wearing a long, cream-colored jacket over a French cuff shirt sans cuff links and with the tails hanging out. He's heading toward an Orson Welles stage of portliness and uses thick cigars to punctuate pontifications on the state of the world.

Vangelis always was a synthesist with orchestral sensibilities, and Mythodea is only his latest incursion into the classical world. Albums like Heaven and Hell, Mask and last year's ?? Greco mixed Wagnerian choirs with Mahleresque bombast and Bachian filigree. Remarkably, he composes and usually records his music in one take, all instruments and timbres in place, with no sequencers or computers. In the days when Vangelis gave solo performances, his concert program had an admonition that "Vangelis does not employ the use of prerecorded tapes or programs during his performance." He might still need such a notice. Demonstrating his keyboards for a film crew, Vangelis draws out voices, flutes, synthesizers and percussion rolling from his fingertips and, apparently, feet.

"There's a complete synthesizer version of Mythodea that sounds incredible," reveals Neely, who had to transcribe it all since Vangelis doesn't write music. "He's got this special customized setup with foot pedals, so he's playing with his hands and his feet, and he's orchestrating as he plays. He feels an oboe, so he'll bring in the pedal of the oboes, and then bring in the strings, bring in the choir, and it all goes on a tape live. All of those great masterpieces of Vangelis, Chariots of Fire, Conquest of Paradise, they've all been one take." "I think it's the only way to shorten the distance between the moment that's called inspiration and the moment of execution," proclaims Vangelis. "I believe that the best thing is that when you have an idea, it's better to have the result immediately without waiting and writing and going through computers and things like that, because it takes ages. And then I'm easily bored."

Of course, Mythodea, with its massive orchestral and vocal forces, would seem to have required more effort. "Mythodea took one hour to compose," claims Vangelis. "It was played from top to bottom,"

Born Vangelis Papathanassiou in 1943, Vangelis has led a career just outside the mainstream. He reputedly gave his first live performance at age 6. He formed Aphrodite's Child and moved to Paris in the late '60s where the band made several recordings, notably the album 666. Based on the Apocalypse of St. John, it included Greek singer and actress Irene Pappas turning St. John's verse, "I was, lam, I am to come," into an orgasmic frenzy over Vangelis' percussion. Leaving Aphrodite's Child, Vangelis went solo, amassing an army of synthesizers and scoring his best-known works, including Heaven & Hell and in 1982, the soundtrack to Chariots of Fire. Controversial at the time as the first electronic film score to win an Academy Award, Chariots has since become a cliché. Of course, that's not Vangelis' fault, and to his credit he has never tried to replicate Chariots.

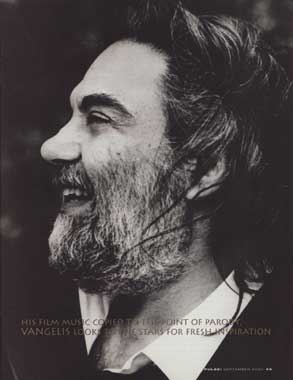

His Film music was copied to the point of parody, Vangelis looks to the stars for fresh inspiration

Mythodea is an ambitious, 10-movement work in which there is actually very little of Vangelis. He never takes a solo, leaving the leads to Battle and Norman. Eschewing both lyrics and the standard chorale solfège of ohhs and ahhs, Vangelis instead constructed his own hieroglyph of phonemes, a la Lisa Gerrard and Adiemus. It wasn't easy for the singers. "Hard time," says Neely. "Well, for them it was a little bit unusual," observes Vangelis. "We shouldn't forget that 90 percent of what operatic singers sing is the classical repertoire and in that they feel much more secure. But the new piece is something that they have to get used to."

They seemed to have no trouble with it in performance, especially on the haunting minor-key refrains of "Movement 9." "What they're singing, what they're saying doesn't matter," says Neely. "It's the expression, and some of those things, 'Orazio,' mean nothing, but when Kathleen Battle sings it, when Jessye Norman sings it, you think, 'I've got to go look that up; what does that mean?' because the way they express it means something." Vangelis is a musician who likes to live in the mystic. "Music just comes to me," he proclaims. "I am like a wire between here and somewhere else." He rarely gives interviews and regrets talking about Mythodea because "we frame the bloody thing, and it's on the wall and it becomes apparent."

"I'm composing with nothing, just nothing,"; he continues. "Total abstraction. No images, not even feelings. With images, feelings, the vision will become subjective, and I try to be as objective as a human being can be." It's curious to hear Vangelis, a man noted for so many tear-inducing themes, talk about nothingness and objectivity in a way that echoes pianist Keith Jarrett or composer John Cage. But like Jarrett, he improvises from a blank slate and, like Cage, he says he tries to take the composer out of the formula, although his instantly recognizable sound belies that notion. Vangelis spent the '90s releasing often-excellent albums into a vacuum without touring, press or label support. Joining the ubiquitous array of such PBS performance specials as Riverdance, Yanni Live at the Acropolis and John Tesh's One World, Sony Classical, at least, is banking on the first Vangelis album to break the surface in 20 years. But despite the media circus and global press junket flown in for the event, Vangelis says he's not really interested. "Without this I would do music anyway, without contracts," he claims. He still remembers the response to albums like 1984's Soil Festivities. "The record company (Polydor) hated it, because it didn't have a hit single," he says ruefully. And Sony is unlikely to find one on Mythodea, but then, this is Sony Classical. It's not supposed to have hit singles.

Interview by John Diliberto

from "Pulse!" magazine